Gordon Wise emailed me out of the blue, having found the Luc(k)raft study on the web. His son-in-law’s father has come into possession of a very large oyster shell which was apparently found on a beach on the Scilly Islands.

The man had actually received the shell in a swap for some comics, and unfortunately he is quite attached to it and doesn’t want to sell it to me!

On the shell is a very careful carving of a funeral procession which shows sailors and marines in dress that indicates the late 1800’s. The ornate hearse portrays a very elaborate funeral. Around the bottom of the shell is this inscription:

In memory of C M Luckraft Lieutenant

HMRNS CORMORANT

age 32 Spirito Santa Island 16 Mar 1882

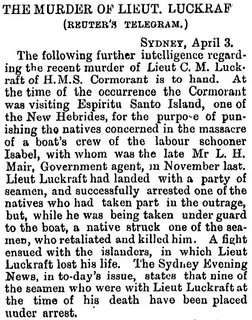

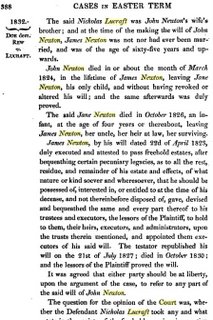

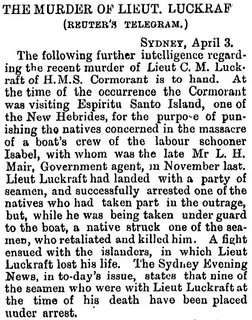

Charles Moore Luckraft has featured before, and if I get a photo of the shell I will insert it into the newsletter. I knew about his death from this report of Charles Moore’s Luckraft’s death on Santa Spirito Island. It is an article from the Wanganui Herald of 1882.

He had been born in 1850, and his father, Commander Charles Maxwell Luckraft, had probably named the young Charles after Captain Moore, who had been Charles Maxwell’s captain in 1845. Charles Moore Luckraft married in 1881 in Greenwich, shortly before he was killed.

The most complete record that we have easily available of these events is in John Bach’s famous book about the Royal Navy in the South West Pacific, from 1821 to 1913. The book is called “The Australia Station” which was the name the Admiralty in London gave to this part of its area of activities. I was able to get a second hand copy from a bookseller in Australia, and below is the extract from the book after a bit of context.

During the 1870s the Navy have been arguing about the powers to punish sailors, citizens and “natives” in the colonial areas where the Navy often had to act on behalf of the Deputy Commissioner who could be hundreds, if not thousands, of miles away.

“This dilemma was highlighted in 1882 when a native held guilty of the murder of a European was brought to Fiji by [HMS] Cormorant. It was immediately evident that no-one knew what to do with him, it being suggested that a special ordinance was needed to allow him to be detained as a prisoner of war instead of being freed as had been his predecessor in 1880. [This was after a punitive action against natives by Captain Maxwell responding to events when six sailors had been massacred, that had caused a great deal of controversy.] On this occasion the idea of an ordinance was rejected on the grounds that it would both exalt the status of the prisoner and detract from his being recognised as a common murderer. It was nevertheless equally inexpedient to release him without any punishment.

“In the event the prisoner, ‘in a state of fear and apprehension’ died in Fiji, just at a time when another captain was producing evidence that would have exonerated him, as well as his original fellow prisoner who had been killed in a fight on the deck of Cormorant soon after his capture. Although Erskine [Commodore] disagreed with the claim that the Fijian was innocent, he nevertheless wrote to Gordon [Sir Arthur, Governor of Fiji] that the ‘unfortunate and lamentable occurrence’ emphasised the possibility of innocent individuals being wrongly punished, a fact which if true would only encourage the natives ‘to take vengeance on the first white man available’.

“This entire affair of the Isabella Massacre at Santo in the New Hebrides in November 1881 became a matter of great importance to the Navy since it revealed clearly the problems it was facing. After hearing of the murder Erskine had ordered Commander Maxwell in Cormorant to proceed against the natives, once identified, by an ‘act of war’, although there was to be no indiscriminate slaughter nor wanton destruction of fruit trees. During the subsequent landing Lieutenant Luckraft was killed by a native shot.

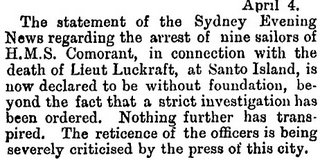

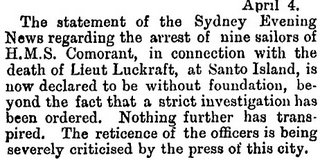

“Maxwell originally took on board two prisoners, but one was killed during a night-time scuffle on deck, the exact details of which never emerged, despite an enquiry. The commander decided to bring the survivor to Sydney against his orders, because he thought any punishment inflicted by him on the spot might appear to the natives to be no more than revenge for Luckraft’s death. Furthermore, being technically a prisoner of war, no significant punishment could have been inflicted on the culprit once in custody.

“The commodore lamented the death of his officer as:

‘.. another in the long list of those who have fallen in the performance of a duty which is constantly forced upon naval officers on this station, but which, however distasteful and hazardous, they would the more cheerfully undertake could they believe that this duty was necessary in the protection of a well regulated and important traffic, and that the sacrifice of their lives would tend in any way to improve the condition of the native races – or to help us to establish better relations between them and the white traders and others who visit their islands.’

“Cormorant’s people had already been involved in the punishment of Lieutenant Bower’s murderers at Florida Island in the Solomons, where they had executed three natives. When Luckraft was killed ashore, the officer assuming command of the party had great difficulty in restraining his men from taking vengeance on all at hand, understandable in the circumstances. The death therefore of one of the two prisoners on board Cormorant was thought perhaps to be a delayed revenge by seamen whose morale was severely damaged by experiences with natives over the past several weeks. It was doubly unfortunate that the possibility of both prisoners being innocent was discovered.

“It was partly because of the sense of guilt caused by this mistake that Erskine’s suggestion made in October 1883, that the chief who instigated the Isabella murders should be found and executed, was rejected by the First Lord who wrote privately to the commodore that given the lapse of time and the unfortunate incident on Cormorant, ‘it will hardly be wise to pursue the course you indicate’. It was a view that was not entirely shared by their lordships, one of whom argued that since the islands were lawless and their inhabitants barbarous, the normal scruples about confusing ‘justice’ with ‘might’ seemed ‘somewhat strained and misplaced’ and prevented justice from being done.”

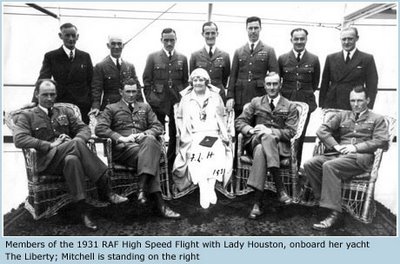

Members of the 1931 RAF High Speed Flight with Lady Houston, onboard her yacht The Liberty; Mitchell is standing on the right

Members of the 1931 RAF High Speed Flight with Lady Houston, onboard her yacht The Liberty; Mitchell is standing on the right